- Blog

- 26 October 2021

What do recent high-profile cases of male violence in the UK tell us about gender norms?

- Author: Emilie Tant

- Published by: ALIGN

Gender norms invisibly influence our lives, maintaining a wide gap in power, resources, and authority between men and women. This is true regardless of where one lives in the world, while still being culturally and geographically specific. Part of the infrastructure that maintains sex inequalities are the social relations and institutions that have been built over time, which end up reinforcing systemic oppressions and social prejudices. The normalisation of misogynistic attitudes has contributed to institutional structures which are blind to women’s needs at the same time as they entrench male power.

The shocking femicides of Sarah Everard and Sabina Nessa in the UK during 2021 have forced a national conversation on the unrelenting reality of male violence. It has generated a rare opportunity to interrogate the very institutions which are supposed to protect women. In this case it shined a spotlight on the alleged misogynistic culture of the London Metropolitan police where Sarah’s rapist and murderer was a serving officer.

Merely six months apart, these horrific crimes have generated extensive media attention in the UK as both women were attacked when they were ‘just walking home’ or meeting a friend. Between March and September, when these two cases occurred, at least 81 more women were killed by men in the UK.

at Sarah Everard vigil, March 2021.

@hannah_walker_brown

What does this tell us about current gender relations, both in the UK and beyond? Not only does it remind us that male violence is a deep-rooted global problem – pervasive in the UK as in any other country, but also that men killing women because they are women remains under-prioritised. And only the most exceptional cases of femicide receive media attention, largely determined by ‘worthiness’ of victims depending on their relation to the perpetrator, race, class, age, and even ‘beauty’. These reporting practices reproduce gendered narratives along with wider social prejudices and discriminations.

What have gender norms got to do with femicide?

A focus on gender norms helps make the link between these fatal crimes and the inadequate responses to them. Following the attack on Sabina Nessa, the local London council provoked backlash by handing out rape alarms and proposing more street lighting as the solution to women’s safety. After the sentencing of Wayne Couzens (Sarah Everard’s killer), the UK’s Home Secretary endorsed a plan for an ‘888 app’ to track women’s movements. But, they failed to initiate a statutory inquiry which would investigate the police culture that led to Sarah’s murder and ensure implementation of reforms.

Calls for women as individuals to keep themselves safe ignore the main feature of men’s violence as a worldwide structural issue based on patriarchal power relations. From catcalls, wolf whistles and groping, to the belittling of women, erasure of their voices and relegation of their concerns to minority ‘women’s issues’ – these gendered normative behaviours create a culture which dismisses women’s lived experiences and upholds impunity for perpetrators.

Even today, when a female is killed by a man, questions are still often asked about her violation of gendered ‘rules’ of public space: ‘What was she wearing? Where was she going? Why was she walking alone so late at night? Was she drunk? Did she resist?’

These questions evidence a culture sustained by misogynistic attitudes which blame women for their own demise. Lord Justice Fulford, who sentenced Wayne Couzens, identified Sarah as a ‘wholly blameless victim’, hinting to the victim-blaming culture deeply entrenched across institutional responses to gender-based violence. The lens of gender norms can help make the link between patriarchal attitudes, women’s sexual objectification and the failure of male-dominated institutions to understand femicide enough to take it seriously.

Sarah Everard and Sabina Nessa: victims of toxic masculinity?

With no country immune, tens of thousands of women and transwomen are routinely murdered across the globe. This begs the question: what is driving this wave of male violence? And why are men around the world not being held accountable?

First, it must be recognised that femicide is at the extreme end of a spectrum of male violence. The normalisation of behaviours towards women such as: leering, sexist jokes, unsolicited ‘dick pics’ and upskirting, stalking, drug spiking, ‘stealthing’ and revenge porn, while considered just part of women’s everyday life, are deeply connected to male power and privilege. One incident can be a gateway to more violent behaviours. Often diminished and laughed at as insignificant, these behaviours hide a much darker side of societal gender norms. They help sustain cultures of harmful masculinities – based on a ‘sexual double standard’ of men’s dominance and entitlement to women’s bodies.

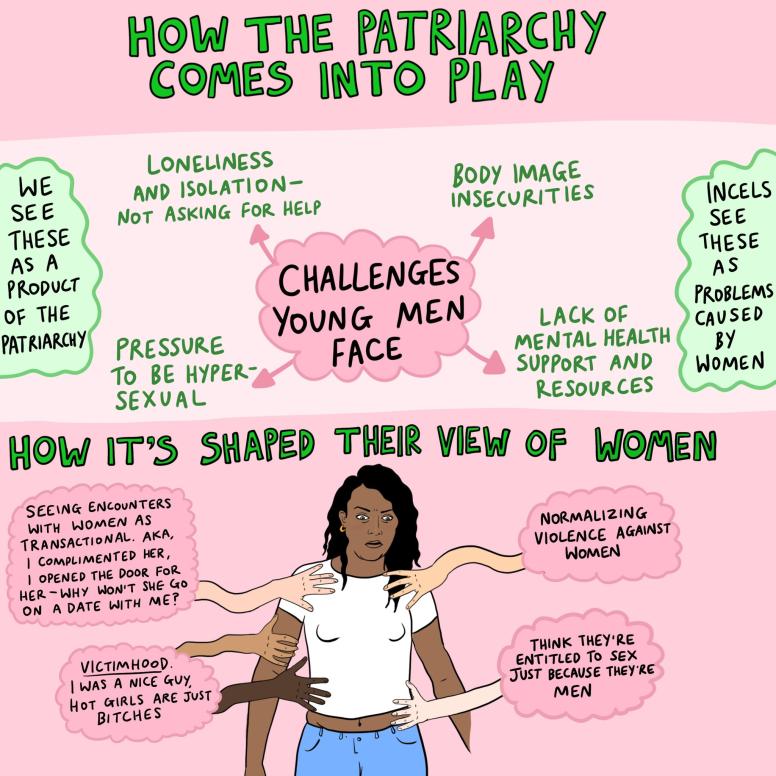

Many societies define manhood in ways that fuel men’s violence towards women as well as other men. Pressures to perform heteromasculinity fall on a scale of microaggressions, to controlling behaviour, to sexual violence and femicide. A gender norms lens unpacks how this is not a natural way of things, but something that is socialised and internalised by individuals to differing degrees.

Media shapes our ideas of the world and how to relate to others, and there are strong sexist messages embedded in the cultural materials we consume: news articles, social media feeds, television shows and films, radio broadcasts and podcast content, online videos, and pornography. Is this in part what drives rape culture and femicide? And are the gendered stereotypes and masculine norms reflected on our screens having an influence on our real-world behaviour? In the case of Wayne Couzens, he was already known to colleagues as ‘the Rapist,’ and had a history of making female police colleagues feel uncomfortable, of sharing misogynistic content and of indecent exposure. It was also revealed that he was obsessed with violent and extreme sexual pornography.

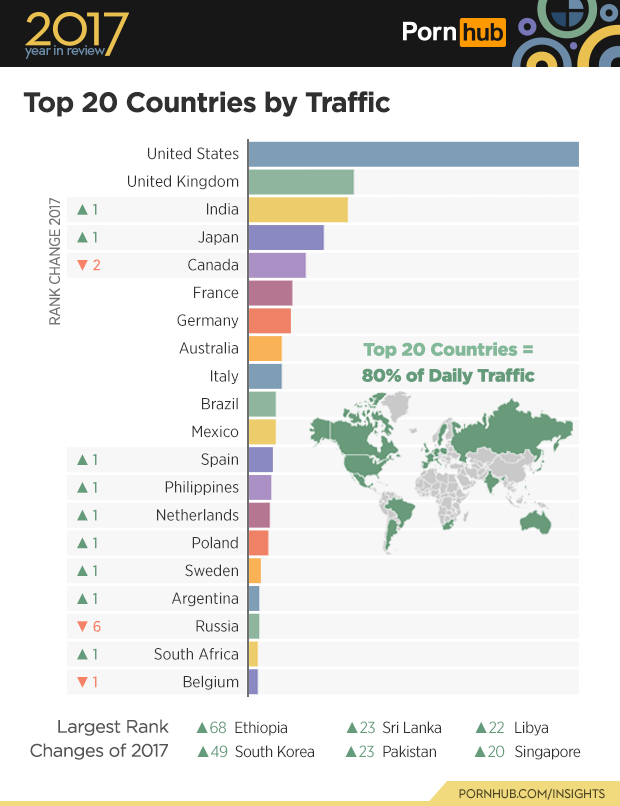

Since the early 2000s, the rise of free platforms all over the globe like PornHub and YouPorn offer 24/7 unlimited streaming to (mostly) men and boys, including children as young as 11. In 2017, PornHub published its site data, recording six billion visits per month translating to 81 million visits per day. Studies analysing porn content estimate that from one in three to as many as nine out of 10 porn videos depict sexual or physical violence - almost always with male aggression directed towards female targets.

The Oxford academic Amia Srinivasan explores the ‘demands of heteromasculinity’ and the ‘rigid gender norms enforced by patriarchy’ both within and outside of pornography. Her work (2021) delves into how these ideas give rise to the radical incel phenomenon with its ideology of male sexual entitlement. This worldview has led incels like Eliot Rogers and Jake Davison to carry out mass killings.

While research is scarce, Srinivasan cites evidence of an overall significant positive association between pornography consumption and attitudes supporting violence against women. More recent studies link violent pornography and acceptance of rape myths, connecting media consumption to what anti-violence activists call ‘rape culture’ (i.e. blaming victims and excusing perpetrators).

Tackling male violence against women through gender norm change

Sexist attitudes and behaviours towards women are inextricably related to the persistence of male violence. But, the links between gender norms and femicide are often downplayed. In the UK’s 2021 Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy, its emphasis on a punitive approach obscures how widely accepted beliefs about masculinity underpin women’s almost universal experiences of gender-based violence. It also fails to name femicide once.

While it has received praise for putting men’s violence towards women on the agenda and integrating support for teachers administering sex education classes, the strategy lacks transformative ambition. It fails to focus on the root cause of violence by ignoring the need to include men and boys in leading a cultural shift away from violent masculinities. Examples from Uganda and Mexico demonstrate how this can be done. These grassroot approaches focus on community-based prevention by engaging men directly. Efforts are based on creating space for unlearning ideas of harmful masculinity and reflecting on the harms of socio-cultural ideas that justify gendered violence.

For male violence to be taken seriously, society must shift attention towards the perpetrators. This includes interrogating ideas of manhood which create the everyday sexism permeating women’s and other LGBTQI+ and gender-nonconforming peoples’ lives. With a gender norms lens, we can begin to actively dismantle misogynistic ideas of heteronormative sex scripts. We can also loosen rigid binary norms and challenge the gendered behaviours which maintain hierarchies between men and women.

About the author - Emilie Tant

Emilie Tant is a Senior Communications Officer at ODI and joined the ALIGN team to support on strategic communication in 2021.

Before joining ODI, Emilie worked across a range of international environments, first in policy and research for the Gender Affairs Division at the United Nations in Santiago, Chile (ECLAC), and later as a consultant for UN Women. More recently she supported advocacy work and youth-led initiatives at the YWCA in Palestine. She has a particular interest in strategic media and research communications to promote global gender justice, peace, and youth-led social movements.

- Tags:

- Gender-based violence

- Countries / Regions:

- United Kingdom, Global

Related resources

Report

5 March 2025

Blog

10 February 2025

Blog

19 December 2024