- Blog

- 16 January 2020

At long last, men’s health has edged on to the global health agenda – and not a moment too soon for those who have spent years calling for more attention to be paid to the health and wellbeing of men and boys.

The issue of men’s health has been highlighted in two recent reports from the World Health Organization (WHO), one on the Sustainable Development Goals and the other on universal health coverage. The WHO European region launched a men’s health strategy in 2018, and the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) has published a report on masculinities and health in the Americas.

Just last year, The Lancet published a series of papers on gender equality, norms and health that discussed the role of masculinities. This was followed by an editorial specifically on men’s health that made a strong case for a sharper focus on the issue.

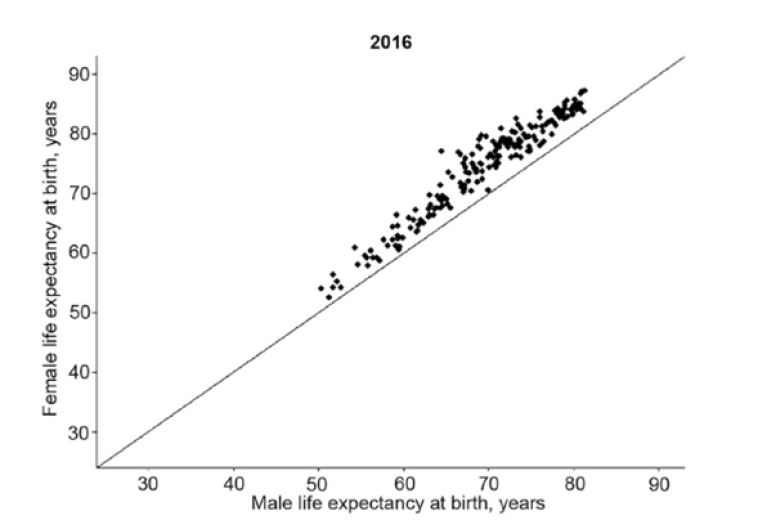

This welcome attention is not simply a response to the many grim statistics about men’s health. After all, these have been readily-available for years. More significant have been the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their particular focus on non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Globally, according to WHO data, the risk of a 30-year-old dying from one of the four major NCDs before the age of 70 is about 22% for men and 15% for women.

The growing interest of men’s health has also been fuelled by the advocacy of civil society organisations across a growing number of countries and internationally, as well as a growing body of research on the psychosocial and biomedical aspects of men’s health, and mounting evidence of how well-delivered services and programmes improve men’s health. What’s more, the adoption of rights-based approaches has focused attention on everyone’s health.

A growing understanding of intersectionality and health has led to a recognition that not all men are privileged and powerful. In the USA, for example, black male life expectancy at birth is 4.5 years shorter than white male life expectancy. Gay men are three times more likely to experience depression than the general adult population and are more likely than heterosexual men to have suicidal thoughts.

We are starting in particular to understand the critical impact of male gender norms on health. The ‘Man Box’ is a useful concept here. It captures the set of beliefs, communicated by parents, families, the media, peers and others, that tell men that they should be self-sufficient, act tough, stick to rigid gender roles, be heterosexual, have sexual prowess, and that they must use aggression to resolve conflicts. Despite all the changes in the lives of men and women over the past 50 years, these rules about what ‘real men’ should do have remained stubbornly in place.

These norms help to explain why so many men take risks with their health. They are five times more likely to smoke than women and over a third of men drink alcohol compared to a quarter of women. Their diets are less healthy than those of women - in Turkey, for example, 81% of men have a ‘poor’ diet compared to 64% of women - and men are more likely to die as a result of a road traffic accident or violence (whether self-inflicted or at the hands of others).

Male norms also lead men to shy away from using the health services on offer, particularly primary care. Men in the United Kingdom, for example, are less likely to see a general practitioner or to take part in health checks to detect undiagnosed cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Across sub-Saharan Africa, men and boys living with HIV are 20% less likely than women and girls living with HIV to know their HIV status, and 27% less likely to be accessing treatment.

There is growing evidence that those men with the most ‘traditional’ gender beliefs are the most likely to take risks with their health and the least likely to use health services effectively. Young men in Australia who conform most closely with the norms of the Man Box are far more likely to engage in regular binge drinking and to have been involved in traffic accidents than young men who do not conform with those norms.

Heterosexual men in the Dominican Republic who are most concerned to demonstrate masculine characteristics were significantly more likely to have had two or more sex partners in the past 30 days and to have never or inconsistently used condoms with non-steady partners.

It is not just the impact of gender norms on men that is problematic. Health policy and services have, for the most part, failed to take men into account; they are simply not responsive to male gender. Just four countries have developed national men’s health policies: Australia, Brazil, Iran and Ireland. There has been an increase in the number of health projects for men, but most of these have been short-term and small-scale and have not led to any significant changes in mainstream service provision.

‘Gender’ must no longer be understood to mean women only. It is also clear that, in the field of gender and health, there is not a binary choice to be made between men’s health and women’s health or some sort of zero sum game. The challenge for public health in the 2020s is to convert the growing interest in, and understanding of, men’s health issues into long-overdue policy and practice as part of an over-arching gender equality framework.

About the author - Peter Baker

- Countries / Regions:

- Global