- Case study

- 29 October 2021

Leveraging the commercial media sector to promote gender equality: The Geena Davis Institute and the Representation Project

- Author: Faria A. Nasruddin

- Published by: ALIGN

The Representation Project and the Geena Davis Institute work with the content-producing side of commercial media, advocating for gender-balance and quality representation on-screen in film and television.

The Geena Davis Institute was founded by the actor Geena Davis in 2004 as a response to the disparity in the on-screen representation of female characters specifically in family entertainment. The organisation carries out research on the state of gender representation in family entertainment media, or entertainment targeted for children and young adolescents, and works with the entertainment industry. It uses its research to drive change that creates gender balance, fosters inclusion, and reduces negative stereotypes of girls and other groups that are under- or mis-represented.

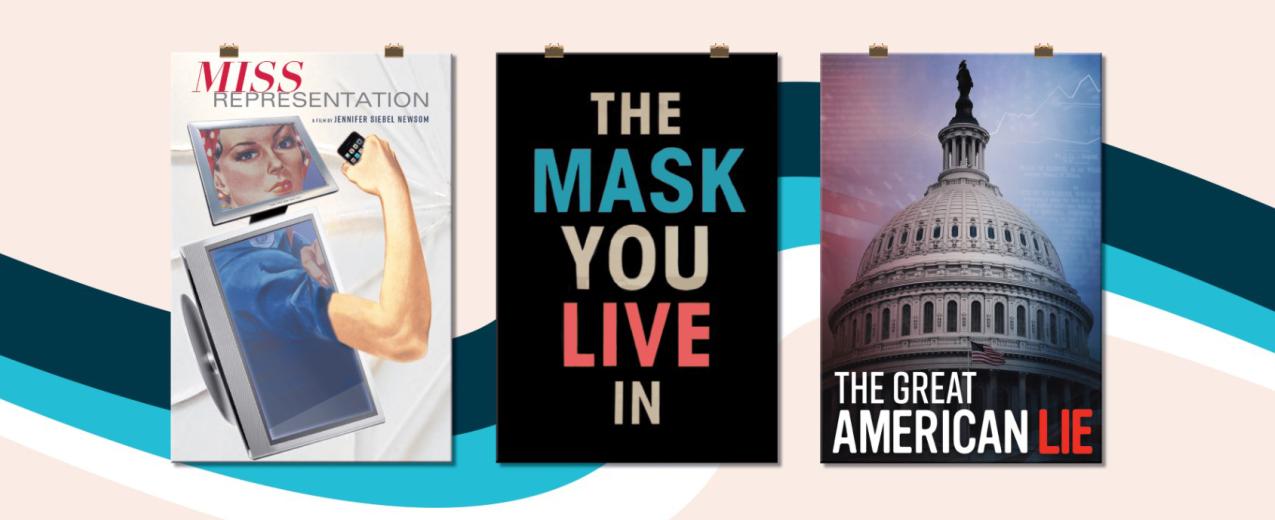

The Representation Project was founded in 2011 by Jennifer Siebel Newson after the release of the film Miss Representation. The Representation Project uses films, youth filmmaker programmes, research, and social media campaigns to fight intersectional sexism and other justice issues.

Theory of change

The Representation Project’s theory of change is ‘if you can shift media, you can shift hearts and minds, you can shift behaviour, and you can shift institutions,’ according to Caroline Heldman, Executive Director. Heldman cites two studies of hers showing that media has an effect on gender norms as the basis for the Representation Project’s approach. In the first, she found that girls were more inspired to go into archery after watching the Hunger Games and Disney’s Brave (a dystopian young adult film series and an animated film, respectively): ‘We saw a massive increase in young girls doing archery and when we asked them why they said it was because of these media role models.’

The second study explored the ‘Scully Effect’, which measured the influence of the character ‘Scully’ from the X-Files, an American science fiction television show from the 1990s. It found that young girls and women who watched the show in the 1990s were significantly more like to go into science, technology, engineering and mathematic (STEM) professions. Furthermore, 61% of women in a STEM profession who came of age during that time cited Scully as a role model and motivator. ‘So, you have some evidence that media has an impact [on gender norms and behaviours]’, says Heldman.

The Geena Davis Institute’s theory of change is based on three pillars: that we all have unconscious biases; that on-screen portrayals are the easiest aspect of influence on unconscious bias to fix; and that industry should make these changes. The Institute believes that if children can grow up consuming a media landscape void of harmful stereotypes and tropes, where girls, boys and non-binary children can see themselves represented equally, then they could appreciate each other’s values and stories and, perhaps, grow into adulthood with fewer unconscious biases. The Institute focuses on children because ‘we have found that by the age of 11 children’s cultural and behavioural beliefs are kind of set and it becomes much harder to unpack that,’ according to Madeline Di Nonno, President and CEO.

Methods

In December 2018, the Representation Project published the first comprehensive report evaluating the impact of Miss Representation, and now the organization has expanded to publish State of the Media and #RespectHerGame reports on gender representation in the media and sports media, respectively.

The Geena Davis Institute’s research ranges from Behind the Scenes: The State of Inclusion and Equity in TV Writing to Gender Bias and Inclusion in Advertising in India and from If he can see it, will he be it? to Historic Screen Time & Speaking Time for Female Characters.

Both organizations are global in scale, but focus primarily on American media, given its dominance in the entertainment market. ‘You have to think about how the United States has influenced so much of the content and also dominates the distribution of content, says Di Nonno. ‘So when you look at native content in certain countries, they can do a much better job when it comes to behind the camera and characters on camera, but when you look at the most successful, a lot of that is still dominated out of the United States.’

As for advocacy, both organizations leverage their research, present it to various leaders within the entertainment industry, and work collaboratively with them to develop programmes. As Di Nonno explains: ‘With each study that we do that begins a cycle of presentations...one company, one division at a time. That could take a year.’ The Geena Davis Institute also conducts sponsored, private research for individual companies to better their on-screen diversity, equity, and inclusion practices.

Similarly, the Representation Project also engages in campaigns and activism, using social media to pressure the entertainment industry to change. In December 2011, for example, the Project launched the hashtag #NotBuyingIt to call out sexist, stereotyped, and degrading advertisements; in February 2016, it launched #BeAModelMan in partnership with Futures Without Violence, Promundo, and Obscura Digital; and in July 2021, the Project launched #RespectHerGame to encourage viewers of the Olympics and other sports to call out sexist sports coverage.

Evidence of change

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Geena Davis institute discovered that their two primary goals were achieved: in 2019 and 2020 the industry achieved gender parity for female lead characters in the top 100 largest grossing family films and the top Nielsen-rated children’s television programming. In terms of specific projects, the work of the Geena Davis Institute inspired Chris Nee, the creator of ‘Doc McStuffins’, to create a new show called, ‘Ada Twist, Scientist’, about an eight-year-old Black girl scientist. In another instance, Mark Osbourne, the director the animated film The Little Prince, based on the children’s book of the same name, put a little girl at the centre of the re-telling and showcasing her interpretation of the original story.

Lastly, the Geena Davis Institute also acts as an executive producer for shows, such as ‘Mission Unstoppable’, because its research has demonstrated the need for more STEM shows in children’s entertainment.

As for the Representation Project, Heldman says there are numerous one-off examples of change in content as a result of the Project’s consultancy work. That being said, change is not yet institutionalised and remains dependent on the goodwill of specific individuals. ‘There isn’t an overall will, it’s just a couple of good people in diversity, equity, and inclusion [DEI] initiatives that are pushing for this; there are some executives who are not DEI that are pushing for this. But I think it’s still very much an individualized effort’, she says.

Looking to the future

Both organizations speak of the challenges arising today when both researching and advocating for intersectional identities. Di Nonno, for example, says that there needs to be more ‘intent’ when it comes to portraying LGBTQIA+ identities on-screen: ‘You don’t need the characters talking about the identities, but you can certainly show same-sex families or gender-fluidity when it comes to depictions. There are a lot of ways to visually depict without making it about the identity—it’s just like anything else. It’s about normalising it. It’s a normal part of the fabric of our community’.

She adds that behind-the-scenes writers and directors in the entertainment industry are ‘storytellers’ who can only speak to their own lived experience, and so portraying a diverse array of identities on-screen means also to ‘fill the pipeline with diverse storytellers’. In other words, on-screen diversity hinges on off-screen diversity.

Heldman, meanwhile, speaks of the difficulties in making diversity an integral component of the entertainment industry: ‘These are profit-centred organisations. They are never going to prioritise representation; they are going to prioritise profit. So, [gender norm change] will never be institutionalised in terms of an institutional will unless it is profit-centred...I think the more you can make economic arguments, the better it is. These are not moral or ethical institutions; they are not going to adopt ethical principles—they might in order to market and tell people that they are doing that’.

On the mainstream, commercial side of the entertainment industry therefore, gender norm change seems possible based on the advocacy of a few motivated individuals, and the work of the Geena Davis Institute and the Representation Project show what can be achieved through a combination of robust research, advocacy and collaboration with commercial media. At present, however, the potential for the widespread change envisioned in the Beijing Platform is not fully compatible with the industry’s mode of business, pointing to the need for continuous advocacy and consumer pressure.

- Tags:

- Broadcast media, Media

- Countries / Regions:

- Global

More case studies

Interview

15 December 2021

Interview

6 December 2021

Case study

1 November 2021

Case study

1 November 2021

Case study

29 October 2021

Case study

29 October 2021

Case study

29 October 2021