- Blog

- 25 July 2024

Gender equality at the Olympic Games: more than just a number

- Author: Emily Subden

- Published by: ALIGN

‘At the Olympic Games, all people are equal, regardless of their country of origin, gender, sexual orientation, social status, religion or political belief.’

Thomas Bach, President of the International Olympic Committee

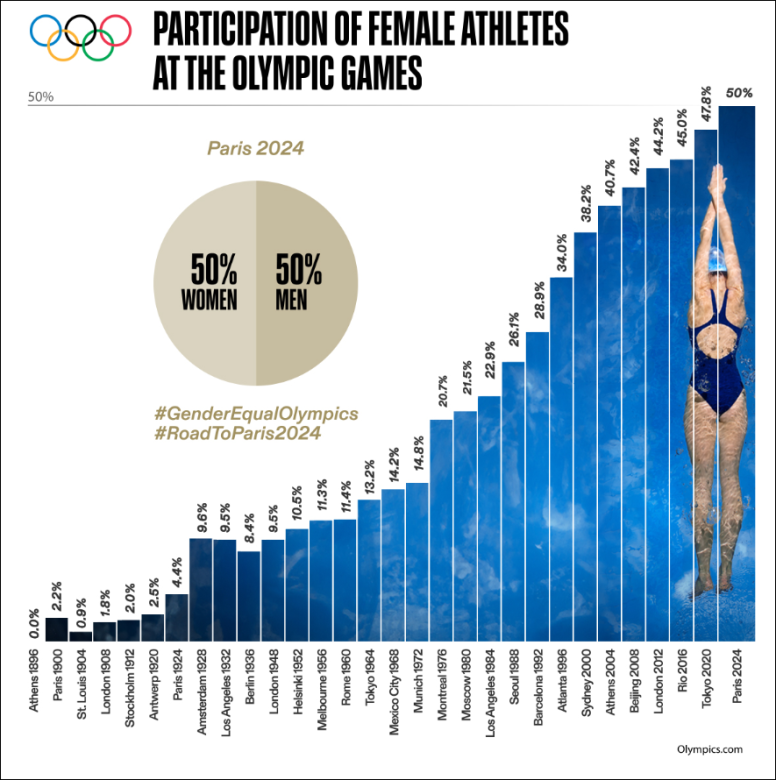

It’s 100 years since Paris last hosted the Olympic Games, and with the number of female athletes rising from a mere 4% across four sports in 1924 to – for the first time ever – exactly 50% across all disciplines, there’s much to celebrate. Even in the three years since the Tokyo Games there has been progress on gender equality in sport both on and off the field of play.

For example, there are now 22 mixed-gender events (up from 18 in Tokyo) designed to ‘embody the equality of male and female athletes on the field of play’. All teams must now have both male and female flag-bearers, and even the logo for the 2024 Paris Games features a woman’s face.

Progress can also be seen beyond the Olympic Games. The gender pay gap in sports, although still wide, is falling. For example, many national football teams, including Brazil, Denmark, Wales and the USA, now pay their male and female footballers the same salary, and FIFA, football’s governing body, has introduced new maternity protocols to support players and coaches.

Recent years have also seen more media coverage of women’s sport. The 2020 T20 Women’s Cricket World Cup was the most watched women’s sporting event ever, with 1.1 billion viewers, and the 2023 Women’s World Cup Football championship was watched live by 365 million people.

Sport reinforcing negative gender norms

Despite this progress, women still face large barriers when it comes to their involvement in sport – many of them underpinned by patriarchal gender norms. Take football, where progress at national level masks an enormous pay gap at club level. In 2023, Leah Williamson, captain of the England Women’s team, earned in a year for her club what Harry Kane, captain of the England Men’s team, earned in just one week for his. In cycling, the total prize fund for the Women’s Tour de France this year is €250,000 Euros, compared to over €2.3 million for the men’s race.

Such gaps reinforce the norm that ‘men are better at sport’, and should therefore be paid more. While the pay gap is not limited to sport, sport has the power to shine a spotlight on this issue. Discussions about whether, for example, female tennis players should earn the same as their male counterparts, open up conversations for other professionals. And as people watch role models such as Billie Jean King, and many other prominent sportswomen, speak out against unequal pay, they may feel more empowered to speak out about the injustices in their own lives.

Sadly, even the achievement of gender parity is not quite the achievement it seems. The Afghanistan Olympics team, for example, complies with the new rule that each country must have a minimum of one male and one female competitor, yet a Taliban spokesperson claims ‘only three athletes are representing Afghanistan’ ignoring the three female Afghani refugees joining them at the Games in Paris.

And in the media, although coverage such as the infamous non-consensual kiss by Spain’s Football Federation President Luis Rubiales on Spanish footballer Jenni Hermoso highlights the widespread issue of sexual harassment and assault, 9 out of 10 elite sportswomen report facing abuse.

When a convicted rapist represents his country in Paris, or the BBC hires a pundit who was convicted of assaulting his girlfriend and has shared posts by misogynist, Andrew Tate, it raises serious concerns about the commitment of the International Olympics Committee (IOC), National Selection Committees, and the media to creating safe, abuse-free sporting environments. This not only undermines their claims to be pursuing equality, but also sets a damaging example for men and boys worldwide.

The role of sport in challenging gender norms

Sport has a multi-faceted role to play in challenging gender norms. From the physical aspects of sport, where norms around the fragility of the female body are challenged and strength, skill and agility are showcased, to travelling to training, creating role models, and challenging expectations around girls and women’s roles within the home, sport can have a major impact.

Sports clubs, for example, are often used in development programmes to provide training or mentoring on other issues such as sexual and reproductive health, child marriage and continued education. Renowned examples from India include Parivartan for Girls, which works with adolescent girls to boost their self-esteem, confidence and educational aspirations while challenging gender norms around their use of public space, the division of labour in the home and their ability to take part in, and enjoy, physical activity. And Maitrayana, which ‘leverages the power of sport to create ecosystems that empower women and girls to fulfil their potential’.

Barriers to women and girls' participation

A study by sports brand Asics surveyed 25,000 people across 40 countries on the barriers to women’s participation in sport and found 51% of women were doing less exercise than they would like, with negative consequences for both their physical and mental health. Male respondents thought the reason for this was body insecurities and fear of harassment, while the women themselves reported the biggest barriers were time and cost, stating they rarely prioritised their own sporting needs over their household and work commitments.

Educating men on the real reasons why women and girls are not as active as they would like to be, challenging norms around household responsibilities and unpaid care work (women do three times more of it than men), and giving equal priority to sport for all would be game changers for women’s involvement in sport. Another would be seeing more women leaders and coaches in sport who are challenging gendered expectations.

The importance of role models

‘With such a large global audience, the Olympics is one of the major events with the capacity to influence the ideas of sports administrators, policy-makers, analysts and spectators worldwide on gender equality in sports.’

Meg Smith, Women Win

Role models in sport not only inspire women and girls to participate in sport, but they also embody the freedom to travel and the strength to pursue ambitions. They are shown pursuing an ‘even playing field’ with men and boys, and prioritising their own health and well-being over traditional household responsibilities.

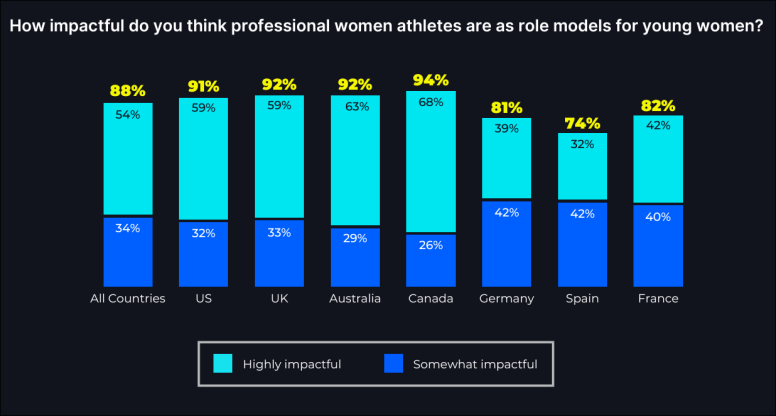

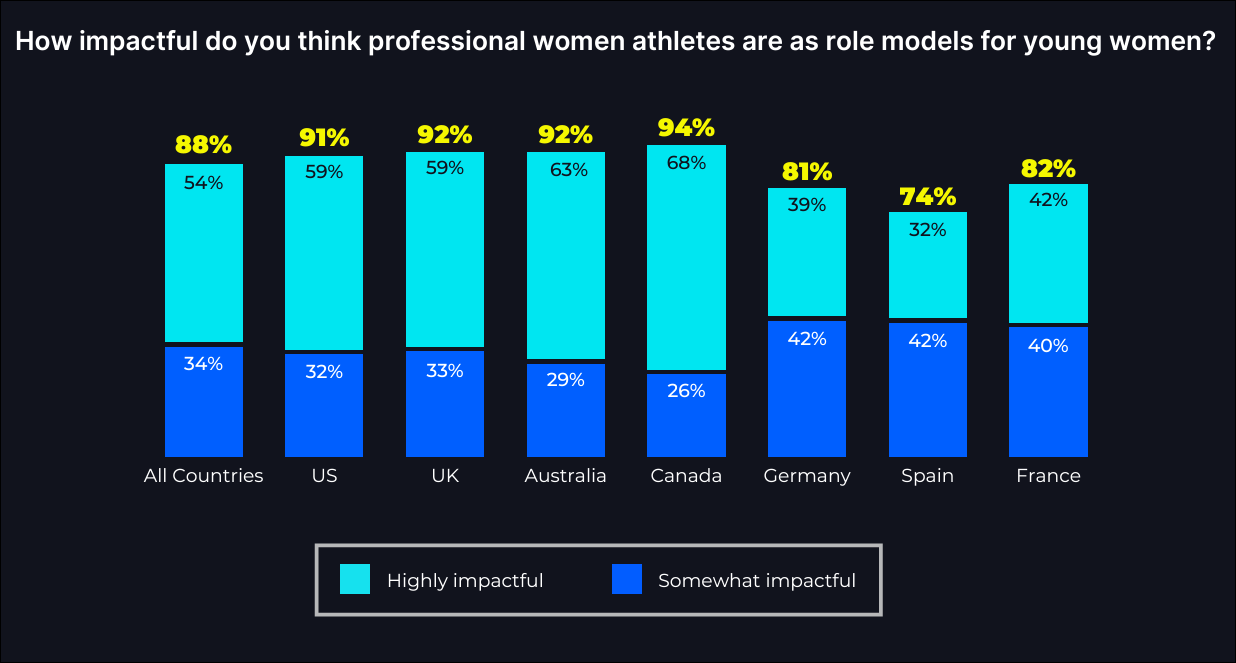

A recent poll by Parity in seven countries found that 88% of those interviewed believe professional women athletes are impactful role models for young women. The media, however, may be lagging behind. Even though 70% of people in the same survey watch women’s sport, a Wasserman study in 2022 revealed that it still only makes up 16% of all sports media coverage.

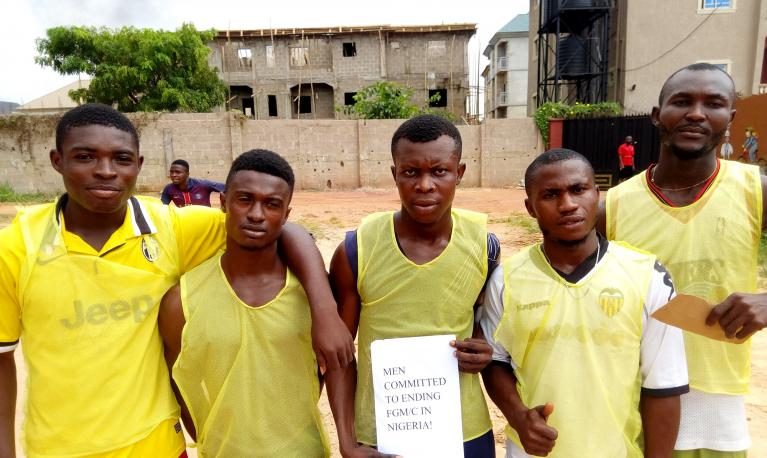

Alongside positive female role models for women and girls, another key component in promoting women’s participation in sport is engaging male allies and, according to a new study by Women in Sport, engaging boys as young as possible in this. The study found gender norms towards sport were already embedded in primary-aged children:

‘When boys are grown up they work and exercise. When girls grow up, they have to stay at home and make food.’

Primary-aged school boy, Women in Sport report

Such views, as well as excluding girls and women, create stigma against boys and men who do not like sport and who are perceived as less manly as a result. The report goes on to say the boys’ views of sport as a male domain are fuelled by men’s domination in sport, a lack of positive male role models who promote inclusion, and a lack of visibility of girls and women who are active in sport, both in the community and in the media.

The most equal Olympics?

‘While we have seen improvements in gender equality in sport, we need more, and quickly. We can’t just arrive at 50-50 representation in competition and say the job is done.’

Marisol Casado, Chair of IOC Gender Equality Working Group

Full gender equality in sport is still a long way off. Recognizing the urgent need for action, the IOC has launched a five-year strategic plan that covers not only participation, but also leadership, safety, portrayal and resource allocation. The sports community will be watching closely to see what impact this has in the coming years.

Sport has the unique power to challenge entrenched gender norms and inspire broader social change. By showcasing the strength and resilience of female athletes and promoting women in leadership roles, it can empower women and girls worldwide. Achieving true gender equality at the Olympics, however, is not just about numbers; it's about fostering an environment where all athletes, regardless of gender, can thrive and inspire future generations.

So will these Olympic Games live up to expectations and be the most truly gender equal Olympics to date? With athletes from 206 nations, plus the IOC Refugee Olympic Team, the eyes of the world will be firmly on Paris 2024.

Share this blog

'Gender equality at the Olympic Games: more than just a number' - NEW #blog by @align_gender.

#genderequalityolympics #changethegame #Paris2024

About the author

Emily Subden is a Communications Specialist for the ALIGN team as well as a keen sportswoman who champions inclusivity and gender equality in all her sporting interests.

Before joining the ALIGN team in 2018, Emily worked for the United Nations for six years focusing on education and children's rights. She recently completed a Master’s Degree in Education, Gender and International Development at University College London (UCL) and her thesis focused on sport for development and sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Related resources

Blog

22 July 2021

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

16 August 2021

Published by: ALIGN, Women Win

Report

10 March 2020

Published by: Women Win, ODI

Case study

9 September 2019

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

14 June 2019

Published by: ALIGN

Briefing paper

1 March 2019

Published by: STRIVE, ICRW

Report

1 January 2019

Published by: ICRW

Journal article

10 April 2018

Published by: BCM Public Health