- Blog

- 9 January 2019

Qualitative data shows how sexuality education can address social norms

- Author: Shelly Makleff, Cicely Marston

- Published by: ALIGN

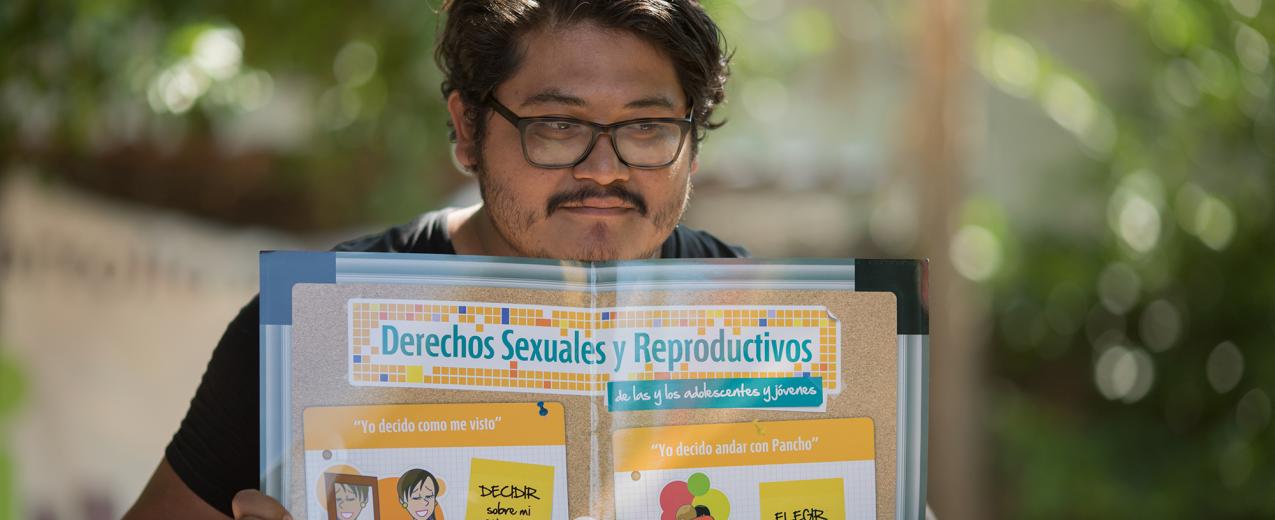

When done well, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has the potential to transform young people’s lives, shifting the harmful gender norms that fuel inequitable relationships, intimate partner violence, unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. To understand how CSE might influence young people’s beliefs and behaviours, three organisations (Fundación Mexicana para la Planeación Familiar, the International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) carried out a study examining a one-term comprehensive sexuality education programme implemented by Mexfam. We gathered data in 2017 and 2018 from secondary school students aged 14 to 17 who participated in the CSE programme in Mexico City.

We also gathered longitudinal data using monthly in-depth interviews during and after the programme. This approach was time consuming, but it had four key benefits. First, interviewees appeared to build trust with the interviewer over months of contact and become more prepared to share personal stories. Second, repeat interviews enabled us to follow-up on topics that had surfaced in prior interviews. Third, frequent meetings with the students taught us more about their daily lives. Fourth, we could learn about both gradual changes and ‘tipping points’ that might not emerge in a one-off interview or through questionnaires carried out only at the beginning and end of an initiative.

Lessons learned

It is too early to assess the programme’s medium- to long-term impact. However, the final in-depth interviews we conducted two to three months after the programme suggest that many participants had retained its information and ideas. Some participants in repeat interviews talked in ways that suggest they had sustained shifts they had described in their earlier interviews, whereas others talked about their beliefs differently over time. For example, one participant said in an early interview that he used to think that jealousy in relationships was acceptable but that the course had changed his views. In another interview, more than a month later, he said he had always believed that jealousy was bad. This example highlights another potential benefit of longitudinal qualitative research: the opportunity to learn about change as it was happening rather than after it had taken place. It also illustrates the challenges of examining a subject as complex and intangible as social norms.

This study in Mexico was funded with the support of Mr. Stanley Eisenberg.

About the authors

Shelly Makleff

Shelly Makleff’s research focuses on sexual and reproductive health. Her work spans gender-based violence, comprehensive sexuality education, abortion, stigma, HIV/AIDS and sexual diversity. She has worked over the past 15 years throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, with additional projects in Asia, Africa and Europe.

Shelly is completing a PhD at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), where her research explores the collaborative evaluation of social interventions in low- and middle-income countries, building on fieldwork in a Mexico City school.

You can find out more about her work at makleffconsulting.com.

Cicely Marston

Cicely Marston is Professor of Public Health in the Faculty of Public Health and Policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Her research interests include interdisciplinary research on sexual and reproductive health, particularly of young people, and community participation in health. She has an overarching interest in methodology, particularly in developing methods to investigate complex social interventions.

She leads the DEPTH research group, and co-leads the 'A' (Adolescents and Young People) Theme of the large, cross-faculty MARCH centre.

Follow Cicely on Twitter at @cicely.

- Countries / Regions:

- Mexico

Briefing paper

18 March 2019

Report

26 March 2025

Report

13 November 2024