- Blog

- 20 novembre 2023

‘Too young’, ‘Too old’, ‘Too emotional’: how gender norms hold women back in local politics

- Author: Ján Michalko

- Published by: ALIGN

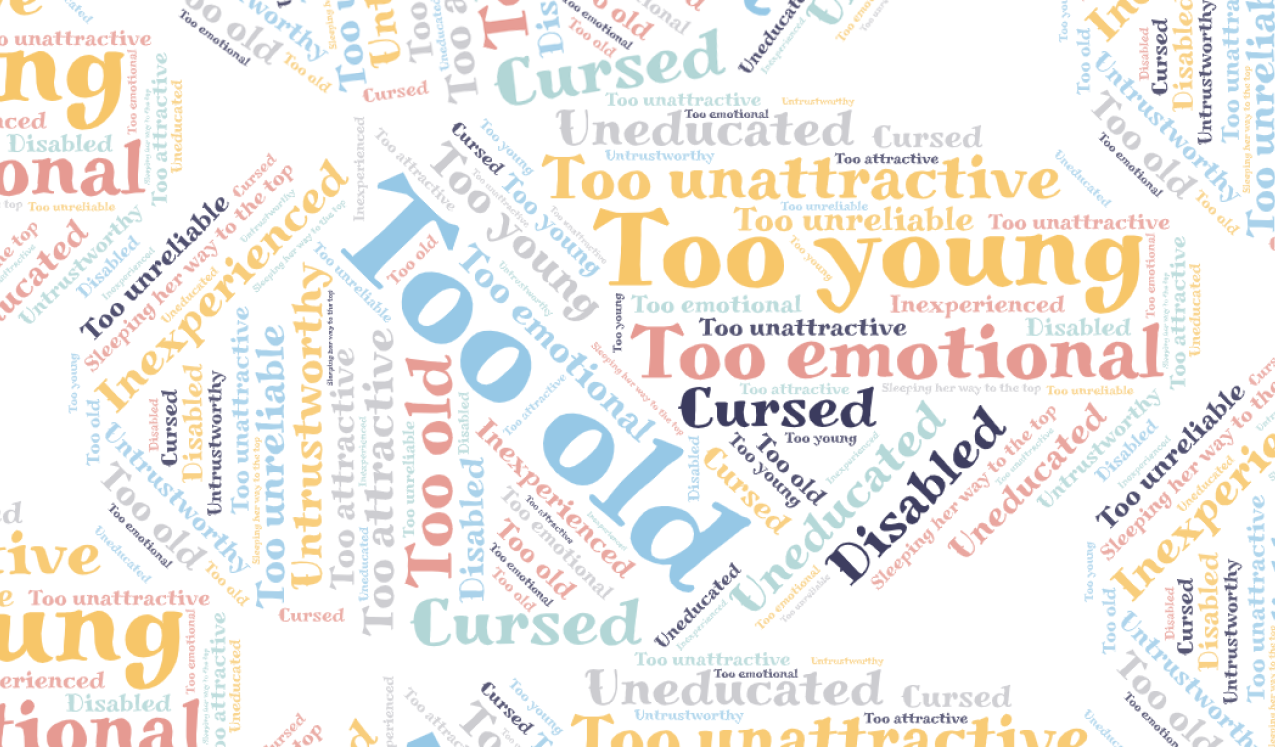

‘Too young.’ ‘Too old.’ ’Too attractive.’ ‘Too unattractive.’ ‘Too emotional.’ ‘Too unreliable.’ ‘Untrustworthy.’ ‘Cursed.’

These are just some of the tropes used to discredit and disempower women across Nepal, Nigeria, Peru and Zimbabwe, which have been shared with ALIGN partners by women running for and holding positions at local, municipal and state level.

ALIGN partners have explored how norms shape women’s political participation, where the gender gap remains one of the most persistent and challenging inequality gaps to close. While women’s participation in local and subnational politics tends to be higher than at the national level, their parity is still, at best, a distant prospect.

Meanwhile, some research suggests that local political and governance structures offer important learning opportunities for women to progress to higher office. It can be easier for them to start their political journeys here because they may already be known in their communities for leading social development efforts, and participation at this level requires fewer resources.

Understanding how patriarchal norms are maintained and how they can be transformed in local politics is, therefore, essential for the achievement of equity and the protection of democratic values. That is why ALIGN partnered with organisations in the four countries around the world, aiming to shed further light on challenges and opportunities for change. Here are five essential insights that emerged from their work.

1. Laws are helpful, but they are not enough

Various laws and policies have been introduced in the study countries to enhance women’s political participation. These include direct measures, such as quotas for women’s nomination to municipal councils in Nepal, or indirect measures that are supposed to make politics safer for women, such as laws regulating online abuse in Peru and cybercrimes in Zimbabwe.

These laws, however, are too rarely implemented or followed. In some cases, this stems from a lack of political will among men in positions of power, such as party leaders. In other cases, there are not enough resources and capacities in law enforcement, while many female politicians, particularly in rural areas, lack the awareness, resources or trust to make use of these legal provisions. Laws can be an important for transforming gender inequalities, but they are not an automatic panacea unless they are backed by resources and awareness raising measures.

2. Men can make or break women’s political careers

Most men in patriarchal societies are socialised into accepting and maintaining norms that give them power. Therefore, they often deploy diverse strategies to keep women at home rather than in public office. This has been the case, for example, with men in the executive who have attacked women politicians’ honour and credibility online in Nigeria.

In Zimbabwe, village chiefs have overlooked women traditional leaders for prominent functions, and research in Nepal has found husbands of women in municipal councils have taken over their wives’ responsibilities and side-lined them from their elected roles.

Invisible gender norms that are infused in political institutions that allow men to act upon their gender stereotypical and patriarchal beliefs and attitudes. For example, seemingly gender-neutral requirements for party nominations in Nepal systematically disadvantage women because political party leaders assume that women are less likely to be elected by the voters. This has also been the case in Nigeria, where politics is conducted behind closed doors and based on patronage relations that women struggle to build without their honour and reputation being put at risk. Alongside supporting women in politics themselves, it is also important to engage men to challenge their own deep-rooted attitudes in their personal and professional lives.

3. Women’s experiences of political disempowerment are shaped significantly by other social norms

While most women face barriers to political participation, these structural gender-based challenges are compounded and contoured by religious identity, ethnicity, caste, class, age, sexuality and disability. For example, while seniority is often seen as a way to gain power in many African societies, where our studies in Zimbabwe have shown that a woman leader may be dismissed as too old and out of touch, or too young and inexperienced if she is not married, or out of place if she has children and holds public office. It seems that there is never a right time for her participation.

‘Go and get married first and head a household...then you will have experience in politicking’” (Nehanda, 2023)

Religious views that portray disabilities as either a punishment or curse or a cause for charity often prevent women with disabilities from getting education and employment or running from office. They may even struggle to obtain the documentation they need to register to vote. Women with disabilities are, therefore, often dismissed as leaders.

To better represent the diversity of women’s lived experiences, policy responses to enhance women’s representation must not only speak to the realities of the urban educated elite – who are often the most prominent female voices in national level politics. They must also reflect the realities of the most marginalised women.

4. Emotional and psychological violence against women by men is a major deterrent

Gender norms often define women’s expected roles and behaviours, which are tied to their bodies, sexual behaviours and motherhood. The use of violence, often sexualised, is a key strategy to keep women out of powerful positions. Women in all four case study countries reported that violent actors target women’s appearances and respectability. This is particularly true for online spaces, where aggressive attackers are emboldened by the anonymity of social media.

Data from social media accounts of Zimbabwean politicians show attacks on women accusing them of ‘failing to be good mothers’, while newspaper reporters accuse women appointed to various Nigerian state agencies of ‘sleeping their way to the top’ or having patronage networks rather than skills and qualifications. Men rarely face such attacks, demonstrating the double standards in reporting and continuing to feed wider public stereotypes.

5. Discriminatory gender norms in education and employment exacerbate political exclusion

Women in local and subnational politics are often highly educated and must have exceptional records and qualifications if they are to counter widely held beliefs that women are not competent leaders. However, even when women do possess these credentials, there is an assumption that they have not earned them fairly.

A host of patriarchal gender norms prevent women from obtaining higher education and well-paid employment in many countries. As a result, fewer women run for local office or can afford to finance their political careers and campaigns.

Norms also have a negative impact on other forms of political capital, such as the networks that women need to compete against the ‘old boys clubs’ that characterise politics. For example, Dalit women in Nepal face the intersecting challenges of their caste and their gender, which means that despite having political seats reserved for them, fewer Dalit women run for office and fewer are supported to do so.

Tackling political inequalities, therefore, requires the reinforcing of interventions in other key sectors. The mapping of gender norms and other obstacles experienced by women in politics has allowed our partners to identify the following tangible steps that governments and donors can support to pursue women’s equality in politics.

What can be done in response to harmful norms and structural barriers?

- Strengthen accountability for violence against women in politics by providing more financial resources to law enforcement actors. This would include changing norms and practices in state institutions, including the criminal justice system, to end this violence.

- Support politicians to increase their understanding and use of laws and the other protection mechanisms that are already at their disposal.

- Advocate for legislation that regulates harmful content online, as well as the design and backend operations of social media platforms.

- Run programmes that support women to build their local and international networks and mentor their relationships with other women and feminist civil society.

- Invest in policies that address harmful gender norms in employment and higher/further education to enable more women to compete for positions of power.

- Fund programmes that focus on men in positions of power – both within political institutions (such as parties) and domestically (at homes of women in politics) – to that sensitise men on harmful gender dynamics and practices.

- Generate evidence about the diverse experiences of women in local politics, which can be used to advocate for policies to enable their greater political participation.

Tweet this blog

Recommended reading -> ‘Too young’, ‘Too old’, ‘Too emotional’: how gender norms hold women back in local politics. Blog and new research by @ALIGN_platform

About the author - Ján Michalko

Ján is an experienced qualitative researcher with more than 10 years of experience in the international development sector. He works on a number of projects at ODI including ALIGN, which brings together global research on patriarchal gender norms and transformative change.

Related resources

6 July 2023

Briefing paper

30 octobre 2023

Published by: ALIGN, development Research and Projects Centre

Briefing paper

16 octobre 2023

Published by: ALIGN, Janaki Women Awareness Society

Briefing paper

2 octobre 2023

Published by: ALIGN, Nehanda Centre for Gender and Cultural Studies

Briefing paper

2 octobre 2023

Published by: ALIGN, Deaf Women Included, Local Development Research and Advocacy Trust

Briefing paper

26 septembre 2023

Published by: ALIGN, TechVillage

Briefing paper

21 septembre 2023

Published by: ALIGN

Briefing paper

13 juillet 2023

Published by: ALIGN