- Blog

- 23 août 2023

Anti-gender ideology in Chile: Sex education is not abuse

- Author: Tomás Ojeda, Pablo Astudillo

- Published by: ALIGN

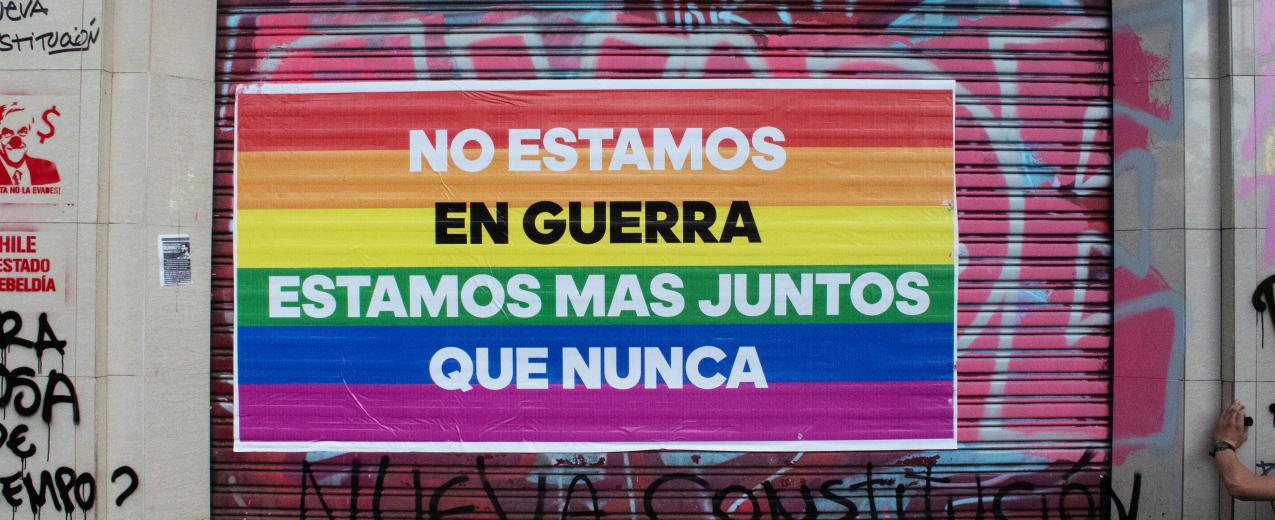

In Chile, anti-gender ideology is being used to attack guidelines on the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in school curricula. Alongside calls to impeach the Minister of Education, there are accusations that the guidelines hypersexualise children and put them at risk of abuse – a script used elsewhere in Latin America. In essence, ‘freedom of education’ – a core neoliberal ideology – is being used to undermine sex education under the guise of ‘child protection’.

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is a key battleground for anti-gender ideology politics in Chile. It warns of the dangers related to teaching about gender, and resists social reforms such as sex education, sexual and reproductive rights and gender mainstreaming. Despite the proven impact of CSE on preventing child sex abuse and driving progress towards gender equality, it has been presented in anti-gender discourses as a threat to the nuclear family and to parents’ role as primary educators. Anti-gender ideology attempts to resist any changes in traditional gender regimes.

Anti-gender ideology and sex education in Chile: A brief history

Conservative resistance to ‘gender’ in Chile has mirrored that seen elsewhere in the region. However, Chile’s debate on ‘moral issues’ and feminism has particular characteristics. According to Nelly Richard, the introduction of the term ‘gender’ in the policy lexicon of the National Woman’s Service (SERNAM) after the 1995 Beijing Conference, ‘was accused of inciting revolt’ by most of the Senate in a context ‘governed by Christian morality and value traditionalism’. Gender was perceived as a ‘contraband’ concept that threatened family stability and heterosexual marriage.

The alliance between the post-transition political parties and the Catholic Church stems from the Church’s support in the fight against the civic-military dictatorship and the power it receives from the ruling elite. Nicole Forstenzer, however, shows that this collaborative pact ‘postponed’ the sexual and reproductive rights agenda in favour of ‘familistic’ and ‘maternalist’ policies to protect Chile’s traditional identity as an alleged Christian country. The Cardinal of Santiago Carlos Oviedo used the expression ‘moral crisis‘ to describe changes in sexual and gender norms in the early 1990s, in a move that has been described as a discursive strategy to retain influence over a particular ‘values agenda’ that centres around the protection of the family. Such narratives continue to haunt the debates on these issues.

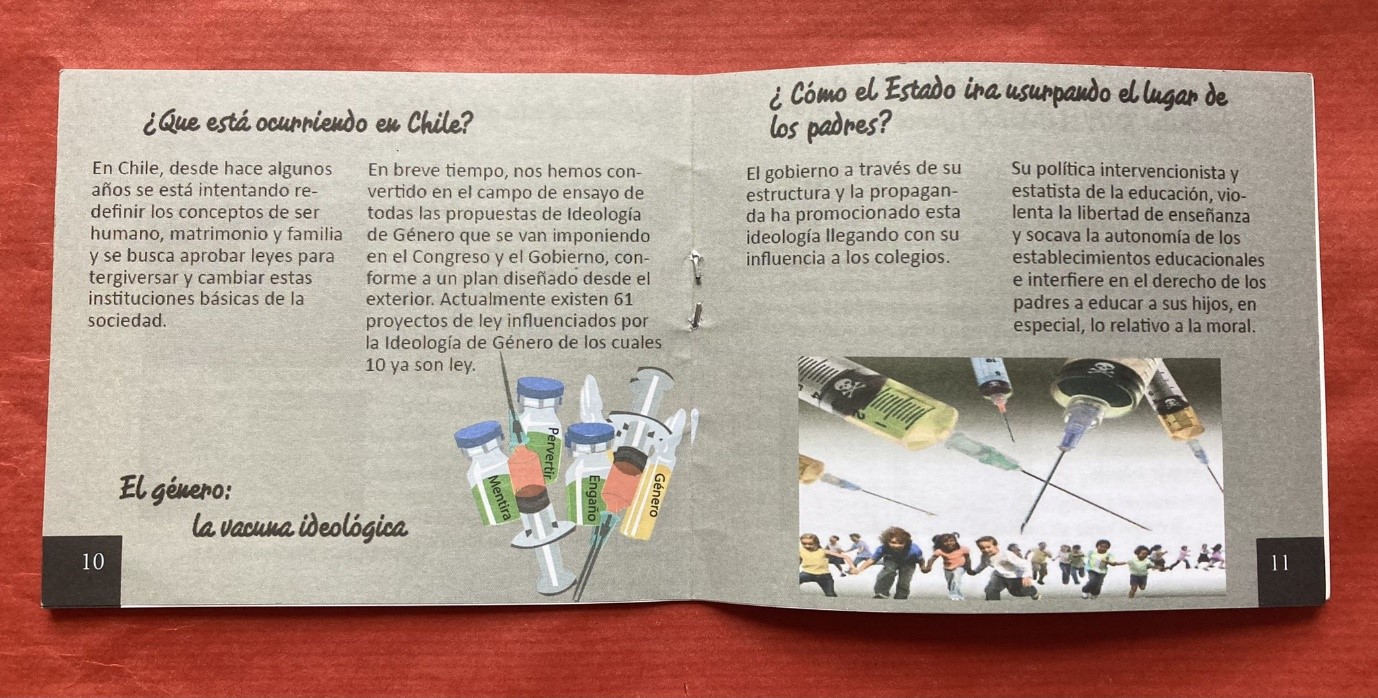

The Church’s influence in public affairs during Chile’s democratic transition and its hold on moral authority has changed dramatically in recent years, with different actors filling this authority vacuum. They include Catholic lay organisations trying to regain their influence and Christian Evangelical churches. Generally, the official discourse of both groups promote an anti-gender ideology, and have gained political influence by constructing an enemy and building a movement around a common agenda. Advocacy strategies aim to mobilise the ‘concerned parent’ as a political actor, attack individuals who embody ‘gender ideology’, and contest gender policies through parliamentary processes, such as the figure of the ‘Constitutional Impeachment’ in Chile.

Gender trouble in Chilean education and the phantom of sex abuse

The implementation of CSE programmes in schools has been contested in efforts to stop ‘gender ideology‘. This conflict dates back to 1996 and the enactment of the sexuality education programme Conversation Workshops on Relationships and Sexuality (known as JOCAS in Spanish). Kathya Araujo notes that the Catholic Church accused the Government of violating the freedom of education principle and the right of families to steer their children’s education, adding that the State had ‘gone too far’, depriving the sexuality debate of its moral character.

Two decades later, we heard similar accusations from new actors, such as the movement Do not Mess with my Children and the organisations Cuide Chile and the Christian Legislative Observatory. In particular, they targeted the inclusion of LGBTQI+ subjects in the educational curriculum following the 2012 Anti-Discrimination Law. The State was accused of excessive interventionism in family matters, and of supporting an ideological agenda pushed by the so-called ‘gay lobby’ and the political left, which sought to homosexualise children and ‘normalise paedophilia‘.

One recent example is the response to the May 2023 presentation of Guidelines for the Protection of the Well-being of Sexual and Gender Diverse Students – part of the national inclusive education policy of the Ministry of Education. Right-wing parliamentarians constitutionally impeached the Minister of Education, an openly gay man, saying that he is ‘obsessed with sexuality’ and prioritising his ‘sexual inclination’ in Chile’s educational debates.

In Chile, anti-gender groups use the principle of freedom of education and anxieties about child sexual abuse to advance their conservative agenda, portraying themselves as the true protectors of childhood and the family. Attacks against CSE express a reactive heteropatriarchal strategy to uphold a specific sex/gender order around the ‘traditional’ nuclear family and produce moral panics by creating a common enemy: the ‘paedophile homosexual’. As Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Korolczuk suggest, equating paedophilia with LGBTQI+ people projects child sexual abuse elsewhere and protects family borders, even though the family is where most of these crimes take place (see also Fundación Amparo y Justicia, 2018; UNICEF, 2017).

Given that the anti-gender crusade is also a crusade to defend ‘the family’, the guidelines and the Minister’s sexuality can be used as scapegoats to maintain the unscrutinised structure of the heterosexual family, even though this model does not represent the reality of Chilean society. This political moment is, therefore, a ‘perfect storm’, combining constitutional debates on the foundations of Chilean society with invocations around an alleged ‘moral crisis’.

Echoing the ‘values crusade’ of the 1990s, the President of the Constitutional Council said in her inaugural speech that Chile is experiencing a ‘deep moral crisis that manifests itself in the breakdown of family life [and] contempt for authority’. In the minds of anti-gender activists, CSE and progress in sexual and reproductive rights contribute to this alleged crisis, threating the authority of the nuclear family. Today’s invocations also aim to reframe the constitutional debate as a ‘moral’ and ‘values agenda’ issue, distracting attention from the issues with the greatest impact on society, such as health, education and economic inequalities, which are a pressing issue under the dictatorship’s Constitution which is still in place.

How can we move forward?

Anti-gender campaigns against CSE worldwide demand a response from political actors to:

- Share local and international evidence on CSE’s impact, enabling actors to dispute the harmful rhetoric that triggers moral panics around CSE.

- Establish sex education policies with budget allocations for their long-term implementation.

- Shift from a reactive funding strategy to one that is long-term and sustainable within State and civil society, aiming for cultural transformation. This strategy must be sensitive to the causes of cultural anxieties around sexuality and gender, highlighting opportunities and best practices, not just the effects of such anxieties.

- Improve communication strategies and involve all social actors, particularly families, to challenge the anxieties around CSE that present it as being opposed to parents or strategies to prevent sex abuse.

About the authors

Dr Tomás Ojeda. I am a PhD in Gender Studies from the LSE Department of Gender Studies, and an ESRC postdoctoral fellow at the University of Brighton’s Centre for Transforming Sexuality and Gender. My research interests lie at the intersection of sexuality and gender theories, psychosocial studies, the study of transnational anti-gender politics, and the histories of the psy disciplines relating to the medicalisation and affirmation of non-normative sexualities and genders.

Dr Pablo Astudillo Lizama. I am a PhD in Sociology from the Université Paris Descartes, France and assistant professor at the Educational Policies Department, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Santiago, Chile. My research interests are mainly focused on gender and educational studies, and on the role of gender and sexuality in contemporary individuation processes in Chile.

- Countries / Regions:

- Chile

Related resources

Report

14 avril 2025

Report

26 mars 2025

Blog

19 décembre 2024