- Blog

- 27 février 2023

"Bang out the machete, boom in her face, grip her up by the neck." Andrew Tate (TikTok).

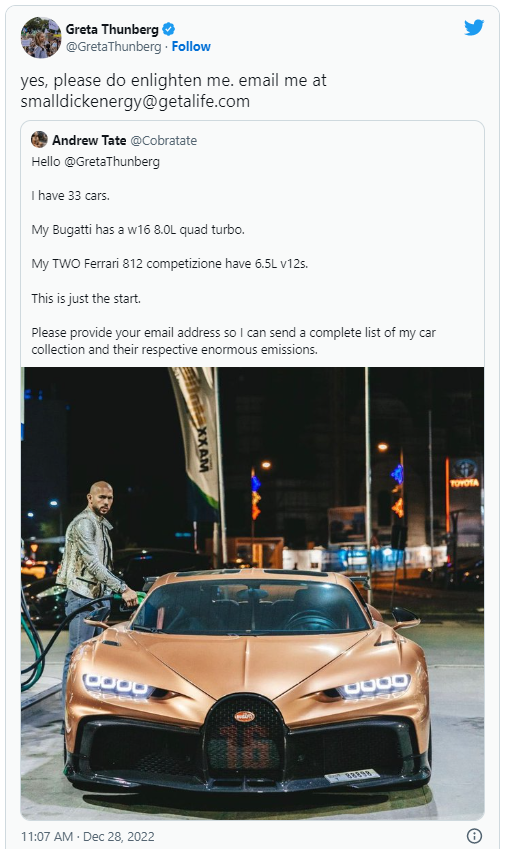

The rise of Andrew Tate as an influencer and his violent misogynistic rhetoric regarding women on social media on Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram has been widely discussed. Tate’s recent arrest in Romania for charges of rape and human trafficking was interpreted as poetic justice after an unprovoked row with Greta Thunberg which was the subject of much mirth on Twitter.

Andrew Tate has amassed an audience of hundreds of millions by positioning himself as an anti-authority figure and rebellious fighter who has become an extremely wealthy and successful man. Tate plays on traditional gender norms to espouse an extreme version of patriarchal masculinity, telling his followers what men ‘should’ be and how they ‘should’ behave. Often termed as toxic masculinity, it is these stereotypes about male breadwinning, physical strength and outright dominance over women that invisibly reinforce unequal power relations between the sexes, and are also a key driver of men’s gendered violence.

Andrew Tate: an outlier or an inevitable product of the manosphere?

Tate’s popularity has been debated and analysed through several angles. But, with over 11 billion views of his content online, his extraordinary reach cannot be denied. The Institute of Strategic Dialogue’s counterterrorism expert, Milo Comerford, situates the Andrew Tate phenomenon within a wider international ‘manosphere’. The ‘manosphere’ is a global online space comprised of a sprawling web of anti-women and misogynistic subcultures including Incels, Men’s Rights Activists (MRA) and Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW), which stretch far beyond the ‘West’. These groups produce a consistent narrative that women are the cause of all their problems in life and borrow terminologies from the 1999 film The Matrix that all of society is a lie.

India has one of the largest numbers of men within the MRA and MGTOW communities and has been called the future homebase for incels. Such misogynistic discourse and behaviour are becoming increasingly common in South Asian online communities. A BBC expose on the secret world of trading nude photos of women on Reddit revealed more than 20,000 of the men trading online and issuing rape threats were from this community.

Some situate Tate’s rise within the broader context of unhappiness resulting from progress towards a more gender-equal world: the idea that the scales have tipped too much in favour of women and men are feeling bereft and do not know their place in the world anymore. This idea, as argued by Monica Gill, is not sufficient to explain the exponential growth in Tate’s popularity and why he has amassed millions of followers, particularly boys and young men. This is because in countries where patriarchy is still firmly entrenched throughout the socio-political fabric (which covers most countries in the world) such as India, South Korea or Slovakia, there have always been angry young men engaging in misogynistic rhetoric and behaviour, irrespective of the Andrew Tate phenomenon.

Is the popularity of Andrew Tate about perception or reality?

An important question Monica Gill asks is: ‘Could it be that it is not actual unfairness, but perceived unfairness, that is making these young men angry? And that this perception is fed directly by the prevalence of sexist narratives in the society in which they live?’

This angle is important because it speaks to how the naturalness of Tate’s misogynistic views are tied up in the language of gender norms. In fact, the 2023 BBC and Vice documentary: The Dangerous Rise of Andrew Tate hears Tate’s inner circle extoll the virtues of ‘traditional gender norms’ with regards to how men can find happiness and should act in their relations with women. This clearly sexist narrative explicitly uses the language of gender norms and demonstrates how patriarchal attitudes are normalised in this way to justify male dominance. It thus makes sense to view Andrew Tate, his persona and what he stands for, from a broader gender norms perspective. This helps us understand how his content taps into pre-existing societal notions of male superiority and female inferiority, driving his global hold on cultural and popular imagination.

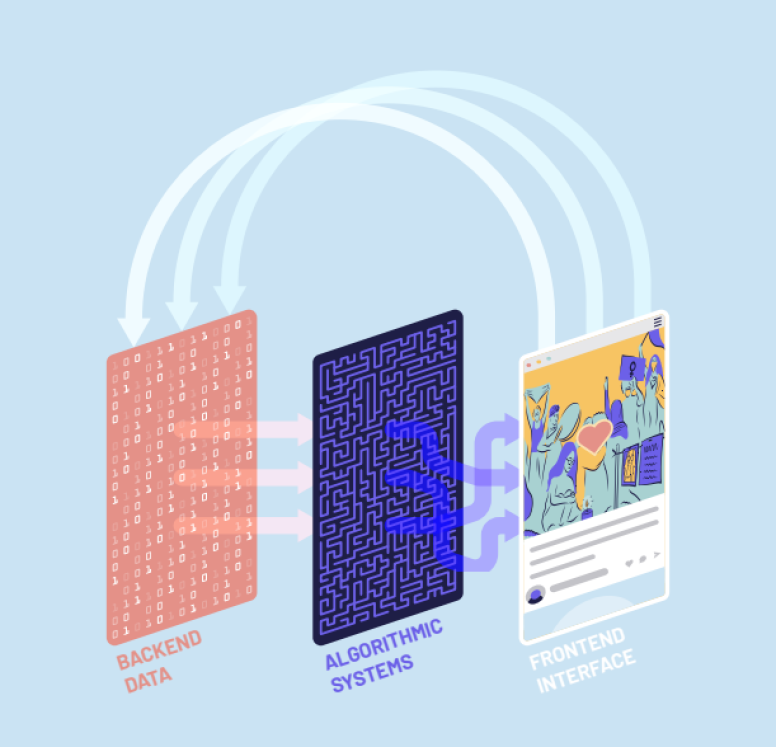

Tate’s popularity and reach, apart from being situated in an international ‘manosphere’, can be further explained by understanding the algorithms of social media companies and how this enables promotion of his videos. His explosive strain of online misogyny is fed by the patriarchal bias baked into technology, as even algorithms of social media platforms perpetuate gender norms, promoting high-engagement content which is also sexist and racist. However, neither the ‘manosphere’ nor social media algorithms alone are a satisfactory explanation for Tate’s popularity among young boys and men.

The fact is that misogyny exists in patriarchal societies, reproduced and expressed through norms that perpetuate deeply embedded attitudes and gendered behaviours. Wider forces, including crises, or a rise in authoritarianism and religious fundamentalism, provide opportunities for unscrupulous leaders, including hyper-capitalists and populist politicians, to target young, vulnerable or disaffected men and boys in support of their agendas. We must not forget that monetizing misogyny and popularising extreme ideas is profitable for some. These are not the only causal factors in deeply complex societies, but they are notable and important.

What can be done about online misogyny?

The Institute of Strategic Dialogue’s Milo Comerford is not wrong in stating that there must be a conversation about why misogynistic content is resonating so much with young boys and men in the first place.

From the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the controversial ruling of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, to the shadow pandemic of domestic violence towards women during COVID-19, Andrew Tate is one piece of a bigger picture, albeit a substantial one. There has to be concerted effort at all levels – government, schools, families and society – to counter gender injustices and misogynistic norms running through all structures of society, which are at the core of global patriarchy.

There are several nascent solutions that can potentially address the harm caused by Andrew Tate's misogynistic discourse. The key is that various actors—governmental and non-governmental— engage in this urgent work to:

- Recognise ‘Andrew Tate-style misogyny’ as a threat in current anti-terrorism policy as well as under hate crime legislation.

- Introduce clear legal frameworks and regulatory mechanisms to counter extremism and impact of inherent patriarchal bias in algorithmic and AI technologies.

- Work with gender experts or facilitators to talk to young boys about norms and masculinity, providing safety containers for them to connect with their emotions.

- Have frank conversations with boys at home about Andrew Tate, particularly fathers with their sons, to inspire alternative role models.

- Conduct workshops with schools and universities on consent and healthy relationships for youth and young adults.

About the author - Dr Gurpreet Kaur

Dr. Gurpreet Kaur is an intersectional gender specialist. She received her B.A. (Hons) and M.A. degrees from the National University of Singapore and has a Ph.D. in Gender and Postcolonial Ecofeminism in Literature from the University of Warwick. She is an endometriosis survivor and was on a wheelchair for five years. Her interest in pursuing international law and policy towards justice was cemented during these years as she experienced first-hand through disability that disempowerment can take various forms and shapes.

She has just finished her LL.M. in human rights, conflict and justice at SOAS University of London, focusing on the conceptions of female violence and terrorism in international human rights law. She also works on gender and disarmament with SCRAP Weapons and is a UN Women UK Delegate to the UN Commission on the Status of Women.

- Countries / Regions:

- United Kingdom, Global

Related resources

Blog

14 avril 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

10 février 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Report

19 novembre 2024

Published by: ALIGN, Mexfam

Report

13 novembre 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

3 octobre 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

30 septembre 2024

Published by: ALIGN, Frente Nacional para la Sororidad

Toolkit

22 août 2024

Published by: Global Boyhood Initiative

Blog

28 mai 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

28 mai 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

17 mai 2024

Published by: USAID

Video/podcast

15 mai 2024

Published by: Now and Men

Report

20 mai 2024

Published by: ALIGN, Centre for Research on Women and Gender, KANITA