- Blog

- 16 avril 2019

Exploring the potential for adolescent girls to disrupt harmful gender norms: Evidence from Africa

- Author: Lilli Loveday, Jenny Rivett

- Published by: ALIGN, Plan International UK

Here we share findings from our latest report, Girls Challenging the Gender Rules, prepared as part of Plan International UK’s qualitative longitudinal study, Real Choices, Real Lives. The study, launched in 2007, has been following the lives of over 120 girls across nine countries in three continents from their births in 2006 to their 18th birthdays in 2024. The study looks at how gender, poverty and age interact with the social norms that shape girls’ lives.

Identifying ‘disruption’ across our data

Our recent analysis, focusing on three African countries – Benin, Togo, and Uganda – signals the potential for gender norms to be questioned, disrupted and even rejected. Previous evidence has suggested that much of the process of gender socialisation, which teaches us the ‘acceptable’ behaviour for each sex, takes place in childhood. This means that many gender norms are already internalised by the time we reach adolescence. However, we see that just before adolescence and during its early stages the Real Choices, Real Lives cohort of girls – aged 12 in 2018 – display attitudes and behaviours that suggest that they are willing to disrupt that process.

An in-depth review of our 12 years of qualitative interview data reveals that all 37 of the girls in Benin, Togo and Uganda had, at some point in their lives, criticised gender norms. They perceived them as ‘unfair’, questioned them or rejected them.

“I don’t do anything [my parents ask me] against my heart and can’t be forced to do things I don’t want to, whatever I do, it’s my decision.” Justine, Uganda, 2017

Given the breadth of the research, covering a range of themes – from education, to social networks, to aspirations – our analysis has explored how girls interact with gendered expectations of them in different parts of their lives. We see, for example, that they have questioned or challenged the roles expected of them in the household, in their general behaviour and interactions with boys, and in their aspirations.

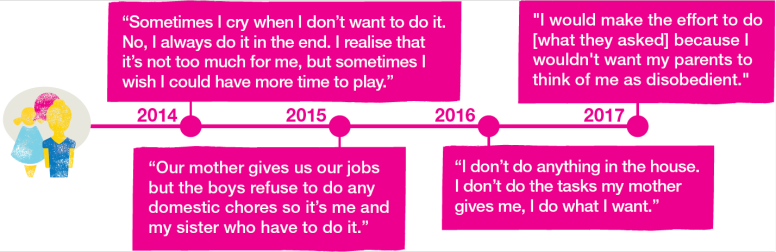

‘Disruption’ is not always linear

This process is not always linear (e.g. notice > question > reject). Instead, attitudes and behaviours can fluctuate over time and in different areas of a girl’s life. The views of Margaret in Benin on housework, for example, have shifted over time (Figure 1).

Social influences and the importance of female role models and representation

We found that social influences, especially in the household and community, were crucial in forming or breaking gendered social expectations. For example, where parents deviated from social norms, their daughters often questioned or rejected gendered expectations – such as Beti, in Uganda.

“Now if I say that only girls cook, it seems so unfair: but previously it was that boys are not supposed to cook. As for me, I noticed that it was unfair, so I decided that everyone should get involved.” Beti’s mother, Uganda, 2015

“No [it’s not fair] …Because the chores women do are more compared to those done by the men… [there could be more balance] by teaching the children discipline and also tell them to do all kind of chores, [whether they are] a boy or a girl.” Beti, Uganda, 2017

The importance of female role models is clear in our data, with visible women leaders influencing not just the aspirations of girls, but also parents’ views on what is ‘acceptable’ and possible for girls.

“My role model is the Rt.Hon. Kadaga I admire her because she has a lot of money and she knows English.” Nimisha, Uganda, 2017

“If you have a woman minister, should you wait for her to come back from her work to cook for you? No! You can’t wait for your minister wife to come home and cook. Everything that men do, women can also do and vice versa.” Alice’s father, Benin, 2017

Obstacles to the disruption of gender norms

The research also reveals the significant barriers to change. Across all three countries, the use of corporal punishment by their elders limits the ability of girls to express ‘deviant’ opinions or behaviour: “I would do it or they would smack me” (Ladi, Togo, 2017). This is a stark example of how household or community environments can prevent changes in gendered social norms. In addition, carers and girls increasingly cite their fears of gender-based violence (GBV) as limiting girls’ freedom to move around in their own communities.

“…the dancing places, going to the borehole at night, and visiting friends late in the evening…Those are the places [girls] end up getting pregnant…The boys can rape her.” Beti’s mother, Uganda, 2017

“Some other people think that girls and boys should move together, even when they go to bath, but others think that when you bath together the boys can rape you.” Justine, Uganda, 2017

Placing the onus on girls to protect themselves by staying at home, rather than addressing GBV , undermines the chances that a girl’s potential to disrupt norms will translate into real social change – particularly if such disruption would put her at risk.

Within the household, particular family members may present barriers to change, even when a girl and others in the household express critical or ‘deviant’ attitudes. There are many examples in the data of women and girls challenging gender norms verbally, but citing men and boys as barriers to change.

“I don’t think it’s fair. If I could change anything I would raise men’s awareness about helping women with the children, I would also make them give money for the cooking to the women.” Ayomide’s mother, Togo, 2017

Some male family members express views that appear to challenge gender norms, but there is little or no evidence of them putting those views into practice at home. This reluctance to make changes raises questions about where gender transformative interventions are possible and effective, how to facilitate intergenerational norm change, and the role of social desirability bias in measuring social norm change.

(Do you think that women are satisfied with what they do compare to what men do?) “No, they are not because they are doing too much so I [don’t] think it’s proportionate and [there’s] no equity in these roles…I can’t handle my wife's chores and roles, so I don’t want them to change.” Jane’s father, Uganda, 2017

Implications for policy and programming

The analysis suggests that three key elements need to be in place if programmes are to support girls in the questioning of gender rules. First, they need programmes that reach them from middle-childhood and into early adolescence to catch their moment of potential resistance. Second, programmes need to be sustained long enough to influence their development. Third, programmes need to adapt and respond to changing contexts, bearing in mind that processes of ‘disruption’ are subtle, non-linear and fluctuating (as seen in Margaret’s views on housework).

The full report is available online, along with a summary. We look forward to drawing comparisons from our forthcoming reports (in 2019) focusing on the Cohort girls living in Latin America and the Caribbean (Brazil, Dominican Republic, and El Salvador) and South East Asia (Cambodia, the Philippines, and Vietnam).

About the authors

Related resources

Blog

19 décembre 2024

Blog

5 décembre 2024

Report

30 septembre 2024